cadibara doesn’t need hype to be interesting. Its appeal comes from something rarer: total competence. This animal survives where land and water blur, holds social groups together without chaos, and shrugs off threats with a mix of patience and physical advantage. Strip away internet jokes and pet café fantasies, and what’s left is one of the most successful mammals in the Americas. If you want a subject worth serious attention, cadibara earns it without trying.

Built for Water, Not as a Gimmick but as a Strategy

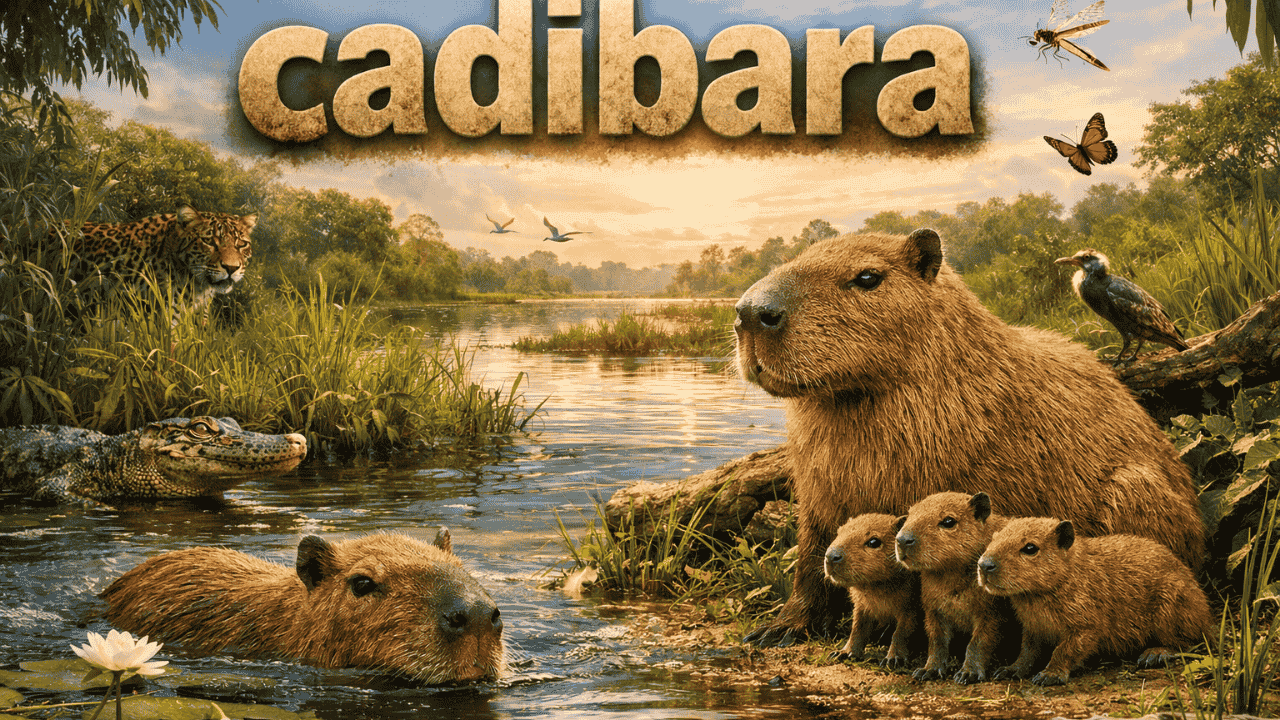

cadibara bodies tell a clear story. Everything about them favors wetlands. Their eyes, ears, and nostrils sit high on the head, letting them stay mostly submerged while watching for danger. Their feet are partially webbed, not decorative, but functional enough to move fast in flooded grasslands and slow rivers.

Swimming isn’t a party trick. cadibara can stay underwater for several minutes, using water as cover when predators close in. Jaguars, caimans, and anacondas rely on ambush. cadibara counters that by slipping into water silently and waiting them out. This isn’t bravery. It’s calculation.

Heat control matters too. Midday temperatures in South American lowlands can flatten careless animals. cadibara spends the hottest hours soaking in water or mud, cooling down while conserving energy. That habit alone explains a large part of their survival rate.

Size Isn’t Everything, but It Changes the Math

Calling cadibara the largest rodent on Earth isn’t trivia. Size shifts the balance in the wild. Adults can exceed 60 kilograms, which removes them from the easy-meal category for most predators. Smaller rodents vanish fast. cadibara stick around.

That mass also supports a digestive system built for low-quality food. Grasses and aquatic plants aren’t nutrient-rich, but cadibara eat a lot of them. Several kilos per day is normal. Their teeth grow continuously, shaped by constant grinding rather than fragile enamel that wears out early.

They also reuse nutrients through a behavior people like to joke about but rarely understand. cadibara reprocess their food efficiently because wetlands don’t offer gourmet options. Survival rewards efficiency, not dignity.

Social Order Without Drama

cadibara groups work because they’re practical. A typical group includes a dominant male, multiple females, juveniles, and subordinate males. Leadership isn’t ceremonial. The dominant male controls breeding and defends territory, especially access to water.

Group size shifts with the seasons. During dry periods, when water sources shrink, cadibara gather in larger numbers. More eyes matter when predators concentrate around the same shrinking ponds. In wet seasons, groups spread out again. No loyalty tests. Just logic.

Communication stays simple and effective. Short barks signal alarm. Whistles keep group members in contact. Low grunts maintain social bonds at close range. cadibara don’t waste energy on complexity they don’t need.

This calm group structure is one reason cadibara tolerate other animals nearby. Birds perch on them. Smaller mammals pass through their territory. cadibara don’t compete unless resources are directly threatened.

Grazers That Shape the Land

cadibara don’t just live in wetlands. They change them. Constant grazing trims grasses that would otherwise overgrow and choke waterways. That keeps open paths for water flow and benefits other species that rely on accessible vegetation.

Their droppings fertilize soil and feed insects, which feed birds and fish. This chain reaction isn’t theoretical. Remove cadibara from an area, and plant growth patterns shift fast. Wetlands become less balanced, more prone to stagnation.

This is where cadibara matter beyond curiosity. They function as quiet regulators. Not apex predators. Not fragile prey. Something steadier, holding ecosystems in working order without drawing attention.

cadibara and Humans: A Complicated Coexistence

Human relationships with cadibara have never been simple. In rural South America, cadibara have long been hunted for meat and hides. In some regions, religious customs even reclassified them as fish for seasonal fasting, a loophole that boosted hunting pressure.

At the same time, cadibara adapt well to human-altered landscapes. Irrigation canals, cattle ponds, and urban waterways often suit them just fine. In certain cities, cadibara populations now live closer to people than ever before.

That proximity creates friction. Farmers blame cadibara for crop damage. Drivers hit them on roads near wetlands. Urban residents alternate between fascination and frustration. cadibara don’t respect property lines, and they never have.

Attempts to turn cadibara into pets or café attractions miss the point. These animals evolved to roam, graze, and manage territory. Confinement strips away the behaviors that make them stable in the first place.

Predators Keep Them Honest

Despite their size, cadibara aren’t untouchable. Jaguars target adults. Caimans ambush from water. Anacondas exploit moments of inattention. Young cadibara face even higher risk, especially during their first months.

What keeps populations stable is not fearlessness but awareness. cadibara choose grazing spots with clear escape routes. They place themselves between land and water, never fully committing to one. That constant positioning is survival math playing out every day.

When danger appears, cadibara don’t scatter randomly. They move as a group toward water, keeping young protected in the center. Panic wastes lives. Coordination saves them.

Reproduction Without Excess

cadibara reproduction reflects the same restraint seen in their social life. Females give birth once a year, usually to four or five offspring. That’s enough to sustain numbers without overwhelming resources.

Young cadibara grow fast, start grazing early, and stay close to adults. There’s no prolonged dependency period. The group absorbs them into daily routines quickly.

This steady reproductive pace helps cadibara populations recover after setbacks without exploding into unsustainable booms. It’s another reason they persist while other large mammals struggle.

Why cadibara Became Internet Icons—and Why That’s Risky

cadibara exploded online because they look relaxed. They sit still. They tolerate chaos around them. That calm reads as friendliness, even consent.

It’s a projection. cadibara aren’t mascots. They tolerate proximity because their survival strategy favors patience over reaction. Push them too far, and they respond decisively.

The online version of cadibara flattens reality. It encourages handling, crowding, and commercialization that doesn’t benefit the animal. Popularity without understanding usually ends badly for wildlife.

Respecting cadibara means allowing distance, not forcing interaction.

Conservation Isn’t About Panic, It’s About Boundaries

cadibara aren’t endangered, but that doesn’t mean they’re immune. Habitat destruction, road expansion, and uncontrolled hunting still reduce local populations.

The smartest conservation efforts focus on wetlands themselves. Protect water sources, limit fragmentation, and cadibara take care of the rest. Heavy-handed intervention rarely works with animals that already manage themselves well.

cadibara thrive when ecosystems function. They decline when humans treat wetlands as disposable land.

The Takeaway No One Likes to Hear

cadibara succeed because they don’t need humans. They need space, water, and time-tested habits. The more people try to reshape them into symbols, attractions, or accessories, the more fragile their future becomes.

If there’s a lesson here, it’s uncomfortable but clear: the best way to live alongside cadibara is to stop trying to own the experience. Let them do what they’ve always done. They’re better at it than we are.

FAQs

- Why do cadibara spend so much time in water even when grazing areas are nearby?

Because water doubles as protection and temperature control. Staying close reduces reaction time when predators appear and prevents overheating. - Do cadibara cause serious damage to farms or crops?

They can damage crops near wetlands, especially grasses and grains, but most conflicts happen where natural buffers have already been removed. - How do cadibara choose group leaders?

Leadership comes from physical dominance and control of territory, not age or size alone. It’s enforced through behavior, not constant fighting. - Are cadibara aggressive toward people?

Rarely. Most incidents happen when humans crowd, corner, or try to handle them. Their calm reputation disappears when boundaries are crossed. - Can cadibara survive in completely urban environments?

Only when water access and grazing areas remain connected. Fully sealed urban spaces eventually push them out or lead to decline.