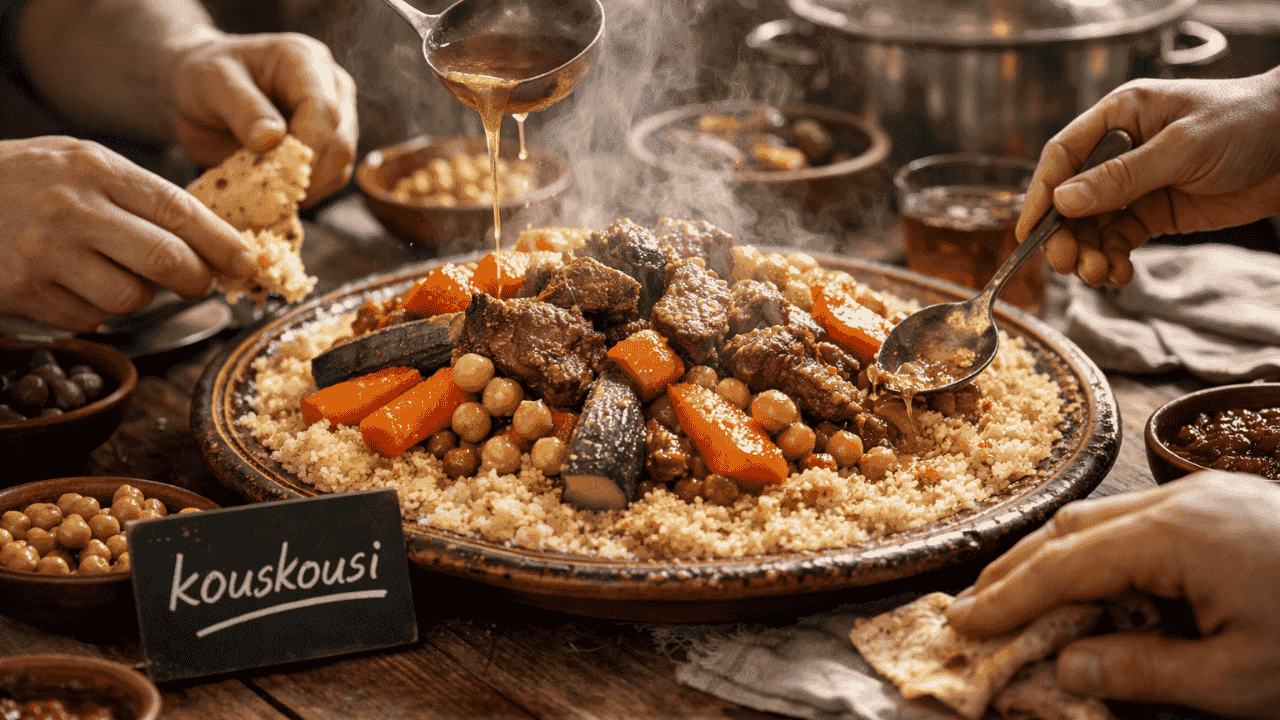

If you’ve ever pushed aside a bland “grain bowl” at a café and wished for something with backbone, you’re really craving kouskousi. Not the boxed side dish tossed together in five minutes, but the real thing—steamed, fluffed by hand, soaked in broth, and piled high with vegetables and slow-cooked meat. Once you eat kouskousi the way families in North Africa prepare it on a Friday afternoon, everything else feels like a shortcut.

Kouskousi carries weight. It feeds entire households, anchors celebrations, and turns a simple table into a gathering point. It isn’t dressed up as health food or marketed as a trend. It’s just dependable, filling, and built to handle big flavors. That honesty is exactly why it has survived for centuries without needing a rebrand.

A dish shaped by land, wheat, and habit

Kouskousi starts with semolina from durum wheat, the same hard wheat used for pasta. The grain thrives in the dry climate across Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia, Libya, and Mauritania, which explains why the food settled there and never left. People didn’t choose kouskousi because it was fashionable; they chose it because the crop grew well and stored easily through long seasons.

The preparation follows the same logic. Semolina is sprinkled with water and rolled into tiny granules, then steamed instead of boiled. That method keeps each piece separate and light. When done right, kouskousi doesn’t clump or turn gummy. It stays fluffy and absorbs broth like a sponge. The texture is the point. You get structure without heaviness, which makes it perfect for soaking up spicy sauces and slow-simmered stews.

Generations refined this routine long before supermarkets existed. The grains are steamed in a stacked pot called a couscoussier, with stew bubbling below and kouskousi cooking above in the rising steam. The two elements talk to each other as they cook. The steam carries aroma upward; the grains capture it. By the time everything hits the serving dish, the flavor has already settled deep inside.

Why Friday kouskousi matters more than any recipe

In a lot of North African homes, kouskousi shows up on Fridays after prayer. It isn’t just lunch; it’s a weekly reset. You don’t plate it individually. You bring out a wide dish, mound the grains in the center, arrange vegetables and meat on top, and everyone gathers around. Hands or spoons move inward. Conversation gets louder. No one eats fast.

That ritual explains why kouskousi holds cultural weight beyond taste. It marks weddings, births, and holidays. Families make huge portions when guests arrive because it stretches without feeling cheap. A pot of kouskousi can feed ten people without anyone leaving hungry, which makes it the opposite of fussy restaurant food.

In 2020, the shared tradition earned formal recognition from UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage list, a nod to how deeply rooted the practice is across several countries. But you don’t need a certificate to feel it. Sit at a crowded table with a steaming platter of kouskousi and you’ll understand in five minutes.

Regional styles that refuse to taste the same

People talk about couscous like it’s one dish. That misses the point. Kouskousi changes dramatically from place to place, and those differences are where the personality lives.

In Morocco, you’ll often see kouskousi topped with seven vegetables—carrots, zucchini, pumpkin, turnips, cabbage, chickpeas, and onions—alongside tender lamb or chicken. Sweet onions cooked down with raisins and cinnamon might land on top, creating a sharp contrast between sweet and savory. The plate looks busy and smells even better.

Algerian kitchens lean into both savory and sweet combinations. You might get a rich red sauce with tomatoes and spices one day, then a celebratory version with dried fruit the next. The grain stays the same, but the mood shifts.

Tunisian cooks push heat harder. Harissa finds its way into the broth, and seafood appears more often near the coast. A spoonful of spicy sauce mixed into hot kouskousi wakes you up fast.

In parts of Libya and Egypt, kouskousi even crosses into dessert territory, served with sugar, butter, or dried fruit. It sounds strange until you taste it. Then it just makes sense.

The takeaway is simple: if you think you’ve “tried” kouskousi once, you haven’t. You’ve tried one household’s version.

The texture problem most people get wrong

Outside North Africa, kouskousi often gets treated like instant rice. Pour boiling water, cover, fluff, done. That approach works in a pinch, but it strips away what makes the dish special. Proper kouskousi needs steam and time. The grains should swell gradually, not shock-cook.

When steamed, each granule stays distinct. When rushed, everything sticks together into a paste. That’s why so many people say they find it bland or boring. They never gave it a fair shot.

Traditional cooks steam kouskousi more than once, fluffing and separating the grains between rounds with oil or butter. It’s hands-on work. The payoff is a texture that feels almost airy, which lets the stew shine instead of drowning the base.

If you care about food at all, this step isn’t optional. It’s the difference between cafeteria filler and something you actually crave.

A practical, filling food that still holds up nutritionally

Kouskousi doesn’t pretend to be a superfood, but it quietly checks plenty of boxes. It’s low in fat, gives you steady carbohydrates for energy, and carries a decent amount of protein. It’s also rich in selenium, which supports immune function and acts as an antioxidant. For something this comforting, that’s a solid deal.

Because it’s based on wheat, it contains gluten, which matters if you’re avoiding it. Still, alternatives made from millet or corn exist, and they mimic the same structure without losing the spirit of kouskousi. The cooking method stays nearly identical.

Compared to heavy rice dishes or dense breads, a plate of kouskousi with vegetables and lean meat feels balanced. You leave satisfied, not sluggish. That’s probably why people have relied on it for daily meals for centuries. It fuels work without slowing you down.

Bringing kouskousi into a modern kitchen without ruining it

You don’t need special equipment to cook good kouskousi at home, but you do need patience and intention. Steam the grains if you can, even if it means rigging a metal strainer over a pot. Season the broth well. Use real vegetables, not frozen scraps. Let the meat cook until it actually falls apart.

The biggest mistake is treating kouskousi like a side dish. It’s the foundation. Build everything else around it. Ladle broth generously. Don’t skimp on spices. This food was never meant to be timid.

Once you get it right, it becomes the kind of meal you repeat without thinking. It handles leftovers well, scales easily for guests, and tastes even better the next day. Few dishes work that hard with so little drama.

Why it still wins against modern food trends

Every year, a new grain shows up with a marketing campaign and a higher price tag. Quinoa had its moment. Farro took a turn. Yet kouskousi keeps showing up on family tables without anyone needing to sell it.

That says something. Food that survives for a thousand years doesn’t stick around by accident. It sticks around because it works. It tastes good, fills people up, and brings them together. Trendy bowls feel lonely by comparison.

If you want one starch that can handle spice, stew, sweetness, and big gatherings without complaining, kouskousi beats almost everything else in the pantry. It’s honest food, and that’s hard to beat.

The next time you’re planning a meal for friends or family, skip the showy recipes. Make a large platter of kouskousi, pile it high, and let people dig in. Watch how fast it disappears. That’s all the proof you need.

FAQs

- Can I cook kouskousi without a couscoussier?

Yes. Set a metal colander or steamer basket over a pot of simmering stew or water, cover it tightly, and steam the grains in batches. It works surprisingly well. - How do I keep kouskousi from turning sticky?

Steam instead of soaking, and fluff the grains with a fork and a little oil or butter between steaming rounds. Don’t drown it in water. - What meat pairs best with kouskousi?

Lamb shoulder and chicken thighs are the safest bets because they stay juicy during long cooking. Beef shank also works if you want deeper flavor. - Can I make kouskousi ahead of time for a party?

Absolutely. Cook it earlier in the day, then reheat gently with a splash of broth or water and steam again to refresh the texture. - What spices make the biggest difference?

Cumin, coriander, turmeric, and a touch of cinnamon build a strong base. Harissa or chili paste adds heat if you want the Tunisian style edge.